7

“If we use how we were taught yesterday to teach our children today, we are not preparing them well for tomorrow.” —Daniel J. Siegel, Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology: An Integrative Handbook of the Mind

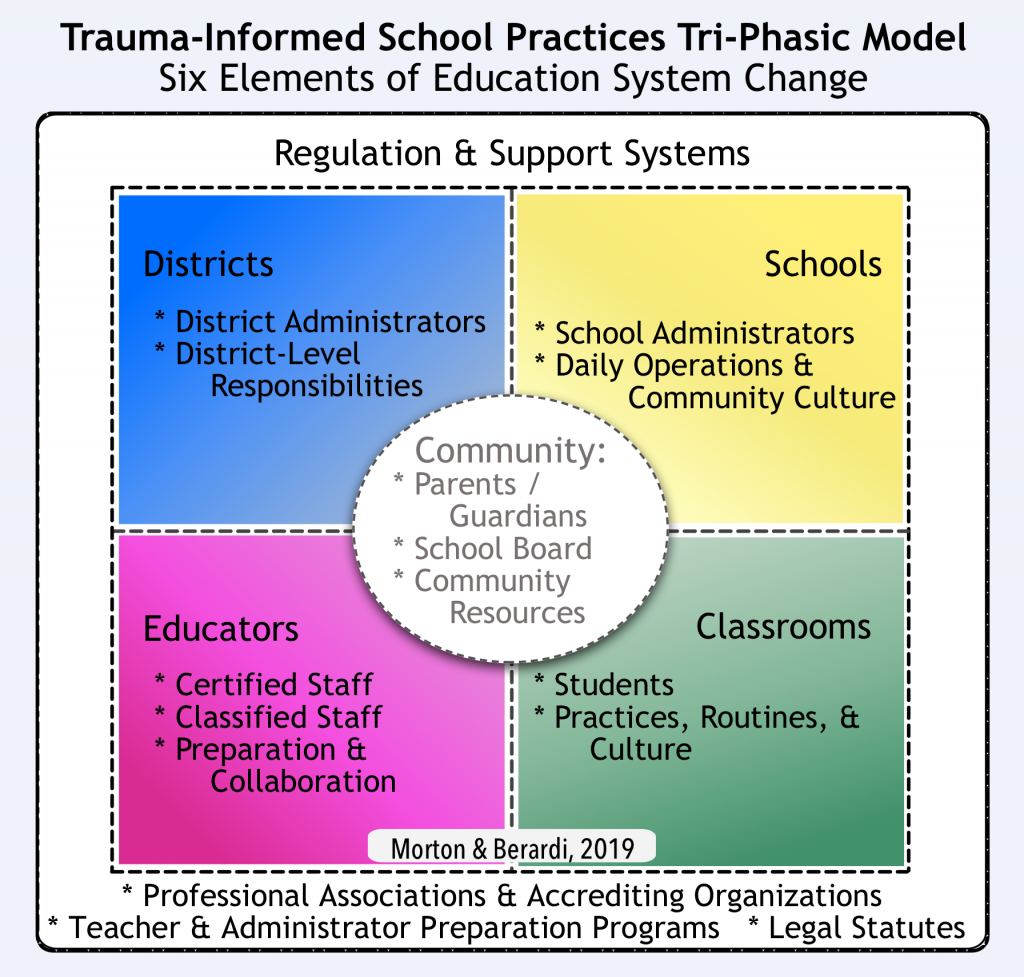

Image Description

The picture introducing this chapter is a diagram of the six elements of education system change corresponding to the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model. The outer box identifies the Regulation and Support Systems consisting of professional associations and accrediting organizations, teacher and administrator preparation programs, and legal statutes. The center of the diagram consists of four adjoining boxes, one each to identify Districts (district administrators and district-level responsibilities); Schools (school administrators, daily operations, and community culture); Educators (certified staff, classified staff; preparation and collaboration); and Classrooms (students; practices, routines, and culture). At the very center of the image is an oval overlapping the four adjoining boxes, identified as Community (parents, guardians, the school board, and community resources).

Desired Outcomes

This chapter invites all layers of the education system to implement preliminary steps towards becoming a trauma-informed learning community. Specific focus is on Phase I dispositions and tasks as applied to Districts, Schools, and Educators. At the conclusion of this chapter, school professionals will be able to:

- Identify specific aspects of your role requiring a trauma-informed shift in perspective

- Gather additional resources to deepen trauma-informed conceptual knowledge as it relates to your role

- Create or join a Strategic Planning Team on the District and/or School level, according to your role

- Develop an Action Plan, with detailed elements of immediate and short-range goals

- Begin implementing Phase I in your District, in Schools, and with Educators

Key Concepts

This chapter provides specific ideas and recommendations for implementing Phase I of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model. Key concepts discussed include the following:

- Transitioning to a TISP learning community first requires a shift in perspective reflecting trauma-informed knowledge and dispositions

- TISP implementation as a developmental process with immediate, short-, middle-, and long-range goals

- TISP invites all school personnel to be aware of isomorphic processes that either model trauma-informed response best practices or undermine the efficacy of TI efforts

- Strategic Planning Teams as a central element for sharing tasks, collaboratively seeking all stakeholder input, and establishing a concrete, manageable, and purposeful developmental trajectory

Chapter Overview

Chapter 6 introduced the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model for education systems transitioning to trauma-informed practice. We identified six subsystem elements that require participation in the transition process in order to promote sustainable and effective trauma-informed learning environments (see Figure 6.1). Sections II and III of this text take each of these six system elements and identify strategies, guidelines, and recommendations for implementing TISP. In this chapter, we address Phase I dispositions and tasks related to Districts, Schools, and Educators. As we address District tasks, we also identify steps to include Community members (caretakers and board members) in planning processes.

Phase I (Connecting) and Phase II (Coaching) of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model are the most labor-intensive phases. The Connecting phase addresses the primacy of attuning to a person’s experience and need, as well as attuning to the larger social setting (using perceptual and conceptual skills), and then acting (executive skills) to convey care, understanding, and safety (both physical and emotional) as a precursor to helping a person or a system move forward with the tasks at hand. These perceptual, conceptual, and executive skills are grounded in attachment theory as informed by neurobiology.

In essence, Phase I perceptual and conceptual skills invite us to examine and perhaps change our perspectives on how we view our learning environments, each other, and our students. These changes in perception are recursive with increasing our mastery of trauma-informed content domains, especially as it relates to stress, neurodevelopment, and their relationship to a student’s capacity to function in the school setting. Chapter 7 primarily focuses on these preliminary tasks related to Connecting perceptual and conceptual skill tasks.

The executive skills of Phase I, the actions we take ideally reflecting the shifts in our perceptual and conceptual schemas, consist of two themes: planning and implementing. Planning is envisioning needed based on what we now know and what we hope to achieve. Implementing is taking action congruent with the goals of Phase I according to our roles. In this chapter, coinciding with identifying preliminary mindset shifts, we focus on planning and implementing Phase I as follows: In Districts, we invite administrators to form a District Strategic Planning Team, setting the stage for breaking the long-range goal down into phases even as implementation begins almost immediately. For Schools, including administrators and the School Strategic Planning Teams, a similar goal-setting process unfolds, with emphasis on supporting school staff. Chapter 7 is one of two chapters focusing on Phase I for Educators, with and discusses developing the educator’s perceptual and conceptual skills as applied to developing an initial Action Plan, as well as gathering ideas and resources prior to implementing Phase I and II strategies with students, whether in the classroom or throughout the school system. Chapter 8 addresses specific implementation of Phase I executive skills in the Classroom by teachers (Educators), with special emphasis on Connecting skills with students.

For each subsystem discussed, our planning implementation recommendations will directly mirror the dispositions and tasks identified in Phase I of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model. We invite you to read Chapter 7 with the TISP document open, and pen and paper at hand. Let’s begin an implementation plan together.

District

This element of the education system refers primarily to district-level administrators and staff, with the recognition that most decision-making processes related to TISP implementation reside here, most notably with the district superintendent. District administrators are also responsible for setting the relational tone of a district. You are viewed as steering the ship; all personnel seek to understand your intentions and anticipate your next move. Districts are the ultimate voice of the learning community and the most likely liaison between Community (as represented by school boards and parents) stakeholder concerns and school personnel charged with responding. And while Schools and Educators may have the most contact with caretakers (parents and guardians), Districts are ultimately accountable to the parents of the students in their care.

For district personnel, if we could take your pulse right now, a reading which indicates your own level of interest in implementing trauma-informed practice within your educational system, what might it say? A low reading might suggest that you are skeptical of the idea, even though you may see the logic in elements of the mindset. Perhaps the overhaul is too expensive, timely, and uncertain. A moderate reading may indicate that you would love to see a district or school transition to trauma-informed practice, yet you are too aware of the systemic elements that could make or break the process at any point along the way. Or, your pulse may be quite high, resonating with the rationale and wanting this for your students and staff in response to the crisis all levels of the system are experiencing right before your very eyes.

We think there is wisdom in every perspective, a grain of truth in most lies, and a falsehood in most truths. The same applies here. TISP does require much heavy lifting with no guarantee of sustained better outcomes for students and educators despite data to the contrary emerging from trauma-informed schools (Berger, 2019; Crosby, Day, Somers, & Baroni, 2018; Jones, Berg, & Osher, 2018; Mendelson, Tandon, O’Brennan, Leaf, & Ialong, 2015; Stevens, 2012). There are many factors that may sink a district’s best efforts, but they will not include poor choices made on your part if you are armed first with TISP conceptual and perceptual knowledge. We need the skeptical to walk beside us, as their insight may be just what is needed when we get stuck, even though we will jump into the work before us trusting that the data and the current state of affairs demand we change course.

First Steps

Having taken a deep dive into the reality that students with unintegrated neural networks are overwhelmed and unable to adequately respond to the developmental demands of the academic environment, you are now ready to make some changes. You have been hearing throughout this text that the problem of inadequate neural development cannot be solved by a few teachers employing basic trauma-informed classroom strategies, even though it may be helpful for that teacher and their handful of students during that given day or class session. You understand that the educational community needs to change. We start this process with a few preliminaries as you begin charting your course.

Take It One Step at a Time. Map out the long-range process. Break it down into phases. Then dig into just the first steps of the immediate goals (this chapter).

Trust That You Are on a Journey. And you are going to be taking your school community along with you. Soon, each segment of the system will be working through their own process of dissonance, skepticism, interest, hope, and excitement.

Don’t Go It Alone. Consult with other district administrators who have decided to transition to trauma-informed practice. Find ways to rely on each other for mutual brainstorming and support. Talk with administrators who have made the switch; they are full of wisdom about glitches and gains along the way.

Keep Reading. Read more about neural integration and learning, about stress and trauma, about schools who have become trauma-informed. We list resources as the end of each chapter linking you with additional trauma-informed educator materials.

And Read Some More, Specifically Relevant and Reliable Leadership Resources. Consult administrative leadership resources about how to nurture systemic change using methods congruent with the culture and ethos of trauma-informed practice. You have read how trauma-informed practice, regardless of setting, invites the professional to embody the heart of its findings. Briefly summarized, having moved beyond mere theories of the social and behavioral sciences, various philosophies, and belief systems, we can say with scientific certainty as revealed in advances in neurobiology, that community is life-giving and crucial to nurturing well-being, health, and consequently, productivity (Cozolino, 2013, 2014; DeCocio, 2018; Siegel, 2012). The relational stance of TISP (attachment as attunement and mentoring between adults and children, and attunement and mutuality between adults) is not merely good for students, but school personnel as well. These relational values are key to sustained health and productivity for each person throughout the lifespan.

Reach for resources that invite a collaborative leadership style that includes employee voices. This is what your building administrators and classroom teachers will be invited to do in relationship with their constituents. Reach for leadership models that acknowledge how being truthful and forthcoming promotes a sense of safety, paving the way for accessing effective coping resources. This is the work of classroom teachers, mirroring what a child knows— yes, life is hard, scary, unfair, and unpredictable, but we are going to find our way through this together.

By forthcoming, we mean discussing the harsh realities along the way as you see it from your vantage point, as well as realities that are of importance to your staff. Last year, we heard a story from a district that had an unprecedented number of tragedies strike its community during summer break. This included the deaths of multiple students and teachers, and life-threatening injuries and illnesses to additional students and staff. These traumas resulted from separate incidents ranging from sheer accident, to acts of violence, to human bodies just failing unexpectedly from time to time. Staff and students were pulsating with grief, fear, and sadness. And not one administrator said a thing! Crickets!

Think about that for a moment. Stress and trauma tap on our implicit and explicit memory circuits. To make sense of an event, we need to process it—not just what happened in the here and now, but with the understanding that current stressors reach into our reservoirs of memory. Each time a significant event impacts a community and that community thinks it is better to not discuss it—for whatever reason, be it legal concerns or just not wanting to bring more stress to people—that community’s silence is deafening. However, when we create space to verbally acknowledge an event or a current stressful or traumatic reality (not force a discussion or debriefing), and we empathically attune to what members of our community might be experiencing, we are seizing a golden opportunity to promote community cohesion, healing, and growth.

This mindset is inviting you to perhaps get out of your comfort zone, as you are being asked to relate to your staff in the same way classroom teachers will be relating to their students.

Trust in the Power of Role Modeling. A system’s view of social change relies heavily on the observation of how patterns of attitudes, as displayed in verbal and nonverbal communication or actions, reverberate throughout a system. In Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecosystemic model of human growth and development (see Chapter 10, Figure 10.1), he captures this same sentiment when describing how the overt and covert values and mores of a culture are the most powerful contributors to identity formation and a sense of well-being. Just like a yawn is catching, so are the covert and overt values of persons with great influence in a system. As systems’ therapists try to help organizations understand how to change their culture, or how to make sense of a relationally toxic element, or break a pattern or habit that members of a system seem to keep cycling through season after season even though its members may come and go, we are looking for what we may call parallel processes or isomorphic patterns (Bernard & Goodyear, 2018; Falender & Shafranske, 2004; Todd & Storm, 1997). When you set in motion a series of actions congruent with an internal attitude and covert beliefs, that becomes a pattern (in attitude and action) likely to be picked up by those around you, whether they can clearly articulate it or not. Actions incongruent with an unspoken attitude are immediately perceived, sometimes in nonverbal ways, as confirmatory messages reflecting the inner attitude. For example, when a person or an organization promotes care for you but you pick up relational values that are to the contrary, the incongruence is merely revealing more about the ultimate inner message. More concretely, it is the proverbial shout of “No, I’m not angry!” Okay, we know you are angry and are having a difficult time owning up to it.

All that to say, as you convey your genuine hope that we can be effective community members with our students who are most impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma; as you pledge your commitment to learning right beside your staff; as you convey patience for the learning and implementation process, which stems from your own inner sense of calm and hope; all of that will be catching. Your staff will feel that each step of the way is manageable. Fear of failure or the stress of the urgent lessens in intensity, even though you are still feeling the pressure of not quite being sure or ready. A sense of hopeful community energy begins to creep into the workplace. This, by the way, is the exact energy classroom teachers will be seeking to build with their students: congruent, honest, caring, attuned communication lessening fear and inspiring hope and other coping resources.

Hold Things Lightly. This is a tough one. TISP will be inviting you to eventually re-evaluate most things you take for granted or have worked tooth and nail to implement and make a success. It reminds me (Anna) of decisions to buy a new piece of furniture or paint walls. The synergy of how things used to work together suddenly does not fit anymore, causing a domino effect of problems. But when the remodeling is done, it is like new life has been breathed into a space. That is what is likely to happen here. Truth telling now…first up might be a re-evaluation of student behavioral management policies, as this system is intricately linked with the culture and hands-on coaching messages we are employing with students. How we handle dysregulated student behavior—meltdowns, tantrums, threats of violence, acts of defiance—these are just the moments we need to walk through with our students over and over again to give them opportunity to use the safety, stabilization, and insight-building skills we are teaching them in class before we usher them through a repair process. We need to totally reimagine what their behavior means, but most importantly, we need to reimagine how to respond. And yes, it still includes limit-setting, consequences, and boundaries, but the delivery method might be from a totally different ethos than currently used by your schools.

Other systems might need retooling not because something is inconsistent with the TISP ethos, but simply because of the domino effect: Change to one part of a system requires others to adjust. As you move through the process, holding things lightly does require some deep breaths and an assurance that any changes can be thoughtful and well-timed, congruent with the discernment of your trauma-informed strategic teams. But for now, pay attention to your own comfort or lack thereof when you think of treasured systems that might beg for reconsideration.

Chapter 7: Exercise 1

What Are Your Resources?

Reflect on the following questions, either on your own or, better yet, in discussion with another administrator traveling a similar path as you.

- TISP is inviting you to take the long view: Implementation takes time; it’s a gradual process to reach all elements of a system. What about that is freeing? What about that is concerning?

- What trauma-informed resources have you discovered? Ask those around you what they have found helpful.

- What is your leadership style? What resources have impacted you the most?

- What is your internal response when imagining the possible need to change TISP-incongruent systems, or systems impacted by the domino effect? How do you deal with change when that change is imposed upon you by a new paradigm (such as TISP) or some other force other than you choosing such a change? Everyone’s style of response is different, not unlike what you will likely encounter in various pockets of your education community. Pay attention to how you respond to forced change, as a way of empathically connecting with staff who may not be too receptive working through change processes.

- Review the TISP Primary Dispositions #1—5, and the Phase I Dispositions #6—8, found in the TISP Tri-Phasic Model document in Chapter 6. What TISP values and dispositions do you resonate with? What challenges you the most? And what items might invite your concern or skepticism? Share these with other administrators working this process. Or save them for a moment to share with your District Strategic Planning Team as you begin your deliberations.

Partner with Community Resources—A District Administrator’s Reflections

Reach out to the community for support and resources. One of the greatest things about our trauma-informed journey is the high number of community groups that have become our partners in helping kids. Mental health providers, the Department of Health and Human Services, the county health department, health insurance providers, and law enforcement all have a vested interest in improving the lives of children. Early on in our work, we invited community members to join our staff in TISP professional learning sessions, and convened several meetings that included school administrators and leaders of various community organizations. That resulted in both stronger connections between groups and a combining of resources that benefits all organizations.

—Bruce, District Office Administrator

Create a District Strategic Planning Team

The first part of not going solo and working in collaboration with others is creating a District Strategic Planning Team. This team becomes the steering committee for the entire process, even though participants may change and subcommittees will be formed.

Choosing Group Members. Don’t be alarmed by the potential size of your Strategic Planning Team as you read through the following elements of assembling a team. Imagine this team is shaped like a series of interlocking hands, with many moving parts, rather than an encapsulated small band of people. A traditional small team may design large-scale, intricate plans full of scaffolded goals along a leisurely timetable. But the only persons who understand it and are excited by it are the members of that isolated group. Think of this team as key to energizing educators throughout the district who will also be sharing updates and serving as liaisons with School Strategic Planning Teams. The nature of this process and this team does invite an intentional team management process, which will be discussed further below. For now, imagine your team as having many functions, and people are needed to play their part.

When assembling a strategic team, it is critical that your group be comprised of the following:

- Trauma-Informed Participants: This is not a committee for staunch naysayers and those invested in protecting a pre-existing idea or program, although both types of participants might be welcome to attend and speak into various meetings. In fact, a structure of transparency as conveyed in open meetings is a wonderful way to build trust. This is a planning committee that will be required to apply distinct knowledge, skills, and dispositions to the evaluation and implementation of program change; it requires new perceptual, conceptual, and executive skills. The planning team is a group of educators (all roles) who are in the process of acquiring or deepening TISP competencies and want to or will be asked to implement TISP within the district.

- Participants Open to Sharing a Process: Participants willing to learn TISP through mutual readings, continuing education, and conferences will be personally challenged as a part of the trauma-informed professional development process. Team members will need to anticipate that the committee is a place to share how the subject matter challenges and impacts their own worldview and personal experience.

- A Diverse Group of Educators: Diversity on a TISP implementation Strategic Planning Team must take into consideration a number of factors pertinent to the nature of the task:

- The Nature of the Subject Matter—Responding to Unmitigated Stress and Trauma: In congruence with the guiding values of trauma-informed best practices, TISP implementation processes need to be honoring of staff and students. In order to practice TISP as part of the implementation process, we need to hear each other’s stories and the social contexts in which they are embedded. By attuning to each other, we can co-design processes that are honoring and growth-promoting. This process is facilitated by committees comprised of stakeholders from a variety of backgrounds and contextual identities including race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, worldview, age, ability, and other identifiers at risk of being socially misunderstood, unseen, vulnerable, and/or marginalized.

- Representative Stakeholders within Each of the Six System Elements: The District team will be facilitating a “Board to Bus” change process, and therefore needs the insight and assistance of educators inhabiting a variety of roles throughout the district, with some positions possibly filled by state-level education administrators or community volunteers. While the team is diverse and comprised of many persons, remember that the team can be built in stages, with subsystems of the team often working independently from the larger group and utilizing your established communication systems to share updates with the rest of the group. An ideal list of District Strategic Planning Team member positions to eventually fill includes:

- Superintendent

- Data Analyst

- Grant Manager

- Curriculum Director/Director of Teaching and Learning

- Behavior Specialist

- Principals: one each per school level

- Principal or another administrator from a school identified as participating in initial implementation plans

- Classroom Teacher: one representative from each school

- School Resource Officer

- Board Member(s)

- Parent: one representative from each school

- Trauma-Informed Licensed Mental Health Provider with skills in parent-focused groups

- Local Trauma-Informed Training Team: preferably a partnership with a teacher educator and counselor educator

- Representatives from a variety of roles, including special education, school counseling, school support services such as cafeteria, maintenance, and transportation services

- Additional members of strategic significance and/or with high interest

Basic Strategic Team Structural Elements. The superintendent and those persons initially giving shape to the District Strategic Planning Team need to consider the following, either prior to gathering team members or as initial business tended to by the group. Each item will invite its own discernment process by district administrators.

- Increase Incentives and Decrease Barriers: Time, level of effort, logistics, ambiguous purpose and processes, and uncertain potential for results to be implemented are committee motivation killers. Happily, if we plan ahead we can minimize most of these items, increasing the likelihood that educators will find service on a Strategic Planning Team rewarding and worth their time and effort.

- As is embedded in these guiding principles, many of the concerns about time, level of effort, and the purpose of the team can be clearly articulated as key people begin to meet and craft the team.

- To reduce time and logistical barriers, depending on your context, consider rotating meeting location, or using an agreed-upon central location. Vary meetings between online asynchronous checking in on tasks and bi-weekly or monthly in-person meetings. Or, host meetings online. Key to remote meeting is guarding against creating more barriers by poor sound and visibility. Assuming adequate internet strength and meeting application veracity, online meeting barriers are common when blending meeting styles in which a group is meeting face-to-face together and others are meeting remotely without using adequate screens or microphones. Be aware that TISP requires much cognitive strategizing as well as personal connection; if meetings are even more stressed by limits to technology, this will impact group dynamics. You might not have much choice; just find a way to attune to these challenges.

- Make the time commitment a part of a participant’s job, not an additional task to an already maxed-out job description. Nothing decreases interest and builds resentment more than having an impossible job description and then being asked to do even more. Consider how each committee person can let go of something for the duration of their service. For example, perhaps a strategy for protecting time and enhancing a consistent meeting place would be to require various members of the team to work at the district office on occasion, depending on the task at hand. Educators would then be relieved of their daily responsibilities on those days. Allow your context and team to guide you in how to honor and protect your coworkers’ time.

- Invite Membership Rotation: This is a large undertaking, and some potential planning team members may fear eternal consignment while others may enjoy hunkering down for the long haul. Build in permission for each member to reevaluate their team role on a yearly basis, with no pressure to leave or continue as long as the fit is mutual for all. The focus of the team will change over time, also inviting members to reevaluate level of involvement.

- A Plan for Cataloguing and Sharing Information: This large, complex change process and its corresponding Strategic Planning Teams need administrative support from a person designated as the primary coordinator of all logistics and communications. Fully functioning TISP Strategic Planning Teams are often large (in larger districts) and consist of many moving parts, including subcommittees. Often, elements of the team may not regularly connect in person with other parts of the team. A system of gathering summaries available to all committee members will be crucial. Likewise, this role would also track communications that would be disseminated throughout the district, including to Community members. This sharing begins building awareness, interest, and trust.

- Clear Expectations of Time Commitment: This is a new adventure, and the motivation, the nature of your district, and other factors dictate how slow or fast schools or teacher cohorts within your district are interested in acting now. Whatever your context, be clear with your team members, even if the message is “time commitment unknown at this moment.” Logic suggests that meeting frequency may be high initially as the team gets its bearings. Subcommittees may meet more regularly once a short-term agenda has been established. Invite your team to understand that the first phase will be solidifying first steps, and with that comes clarity regarding time commitments.

- A Clear Sense of District Administration Involvement: The team needs a clear sense that district administrators are not just delegating this to others. If the superintendent is merely giving staff permission to learn about TISP and implement strategies in schools and classrooms, the process is going to stall and become ineffective. The team needs a clear sense that district administrators are not just delegating this to others. If the superintendent is merely giving staff permission to learn about TISP and implement strategies in schools and classrooms, the process is going to stall and become ineffective. District administrators do need to learn the content domain, have a regular presence in various strategic team meetings, and contribute their voice in communications distributed to team members and the greater district environment.

- Craft a Team Process Management Plan: As mentioned above, most strategic implementation teams start small but eventually become more complex as foundations are built. Depending on your context, this team could be rather large, with schedules difficult to manage. With all other items described here in place (a plan for sharing information, clear expectations, decreasing barriers, membership rotation, etc.), decide how central committee meetings will occur, the “when, where, and who,” how subcommittees will function, and how each element of the team will report back to the whole group. This might be sketched out by a small group of district administrators, or crafted by the initial team once assembled, or follow an initial structure designed by the district to be re-evaluated once the team digs in. But, this process needs to be crafted, clearly articulated, and utilized.

Strategic Team Initial Tasks. A TISP strategic plan may span a number of years as you envision how to bring consistency to a student’s progression through your school system. It is important to note that when starting anywhere in this process, from teachers eager to change the culture and practices within their classrooms to principals seeking to transform an entire school, student outcomes require our attention to the big picture. Attunement and mentoring are needed across the first 18 years of life to maximize a developing person’s likelihood of entering adulthood ready to cope with life demands. The process of integrating neural networks to enable executive functioning is not a single-dose process: it is continual. The challenge for Districts is to envision how to create a seamless process for students whereby they enter a trauma-informed preschool or kindergarten class and graduate from a trauma-informed high school. The process of integrating neural networks to enable executive functioning is not a single-dose process: it is continual. The challenge for Districts is to envision how to create a seamless process for students whereby they enter a trauma-informed preschool or kindergarten class and graduate from a trauma-informed high school.

The District Strategic Planning Team must also address the risks and benefits of educators in some schools, some grade levels, and some departments engaging in the change process while colleagues and school systems serving the same students are not on the same page making changes. First, the good news: Any changes made will benefit that teacher or staff person and the students they serve. And change most often initially occurs in haphazard, hit-or-miss patterns. The bad news: Partial involvement is a frustrating disaster waiting to happen that is demoralizing to the staff person who has caught the vision and is engaged in the work of acquiring TISP competencies. The work of one classroom emphasizing self-regulation prior to and while learning is undermined by other classrooms or student management systems not embodying the same ethos. Consistency and continuity across the day, across classrooms, and across grade levels are key to success.

Most persons and systems can tolerate almost anything if we know why, and that the discomfort is temporary on our way to fixing a problem. When a clear plan exists to gradually bring all elements of the system on board, if only one department or one grade level or one school can initially start the process, we can rest assured that others will be joining in due time. We can’t build this in a day, but the District Strategic Planning Team does need to see the big picture even as very tough decisions need to be made regarding where to start despite limits and drawbacks.

The initial tasks of this undertaking include the following:

- Agree on common reading materials and training. This promotes a common knowledge base and a chance for mutual reflection. This reading list is not only for the team members, but required reading for all personnel choosing to start the trauma-informed transition process.

- Determine how you want to start. We have observed some districts beginning with a small group of educators, primarily classroom teachers, who are committed to the process and have full support of the district. These districts envision the end goal and support pockets of the system engaging in the challenge in their own style and timing. Rachel’s story below illustrates this type of process. We have also observed districts that have chosen to start with primary grades, for example kindergarten through third grade across a district, giving time to bring successive grades on board, with the goal of creating a foundation for current students. Geoffrey Canada took this approach, including his decision to start with expectant parents and parents of infants and young children, putting them through a program he calls “Baby College”(Tough, 2009). Others have chosen to allow a single school to transform its culture and practices, spearheaded by a principal or administrative team deeply committed to the trauma-informed educator approach. Trust you will jump in according to what is best for your constituents; just remain aware of the larger picture and plan accordingly.

- Design a set of training strategies. There is much to consider here, which we have elaborated on below. In summary, this may include:

- Trauma-informed educator book clubs or learning communities set up by school, grade level, role, or common interest

- Professional development support for trauma-informed educator conferences and training workshops

- District- or state-sponsored trauma-informed educator training events

- Implementation coaching and peer supervision training events

- Expand your team to include key stakeholders in the group targeted for initial implementation.

- Assist school(s) to set up a School Strategic Planning Team, a context-specific version appropriate for schools, and begin the initial implementation plans.

- As part of your short-range goals, identify systems each School team may need to re-evaluate as more staff participate in TI education and preparation activities, versus what systems are best if first evaluated by the District team. Most notable is the need to assess and re-evaluate school- or district-wide behavioral management systems. This is a Strategic Planning Team task force project that will quickly move up in urgency. However, this evaluation process must be facilitated by a cohort of educators in a variety of roles who have completed initial trauma-informed education. This ensures that program evaluations and proposed changes are congruent with trauma-informed student behavioral management goals. We recommend that the planning team create space to consult with trauma-informed education trainers, and perhaps sponsor in-service day trainings dedicated to this topic.

- As your immediate and short-range plans take shape, spend a moment glancing toward the long-range plans to identify tasks that may need attention now in preparation for those far-off goals. For example, this might include developing a plan to further train more staff in varying roles, prepare parent classroom volunteers, and add grades and schools to increase continuity for the growing student.

What Conferences or Trainings Are Right for You?

Trauma-informed educator trainings are increasing nationwide. Are all of these good investments? Quick trauma-informed how-to articles are also trending. We read a one-page article on becoming trauma-informed by practicing active listening. Is that all it takes, or is that most helpful for just piquing interest, or encouraging the experienced trauma-informed educator to not forget a basic building block among many? Given the plethora of books and conferences, and our limited time and budgets, where do we start?

Trauma-informed training is near and dear to our hearts, so much so that we offer a continuing education based certificate in TISP (see Appendix C, Trauma-Informed School Practices Certification Program), as well as a postgraduate certificate in trauma-informed services through the Trauma Response Institute at George Fox University (George Fox University, 2019a, 2019b) (https://www.georgefox.edu/counseling-programs/clinics/tri/index.html). But we are only one option among many good options. The following recommendations are intended to help you invest wisely.

- Build interest among your staff first, rather than overwhelm with quick strategies or deep course content. This might be a series of in-service workshops in which a trauma-informed professional can provide insight into the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on executive functioning in the classroom, and its long-term consequences as exemplified in ACE scores. And then move the group to glancing inside trauma-informed schools to catch a vision of what is possible.

- Once interest is present, provide access for your staff to an introductory trauma-informed education course or workshop prior to amassing implementation strategies. We would never want to certify a teacher before that person absorbs foundational concepts informing educator proficiencies. You would never want a counselor or therapist to offer trauma-informed services before absorbing the knowledge, skills, and dispositions of that specialty prior to practice. Likewise, giving educators strategies before providing the background conceptual elements is irresponsible and a setup for failure. This textbook aims to help facilitate this foundational knowledge acquisition process and guide you to deepen your readings. Another good option is to consult with a trauma-informed training team for introductory trauma-informed CE workshops or university-based credit courses.

- Now your staff members are ready to absorb strategy sessions and workshops even while buzzing with their own creations. Most often, strategy-based trainings are found through trauma-informed educator organizations. These conferences are often expensive. But with introductory conceptual elements already in place, your staff will be ready to more fully appreciate everything offered in such venues, as well as vet what is or is not trauma-informed or appropriate for their context. Besides conferences, think of investing in training videos such as those offered by organizations listed at the end of this chapter under Resources for Futher Reading. Local trauma-informed CE/university course training teams should be able to offer implementation strategy workshops as well.

- Use local trainers for implementation coaching. Educators building TISP competencies benefit from coaching processes within the context of peer-consult groups. This model represents yet another blending of training processes common in education and mental health training programs. The integration of trauma-informed perceptual, conceptual, and executive skills in direct work with students is not strengthened by merely following a series of steps or instructions related to a strategy, but by reflection in consultation with other trauma-informed educators. We have utilized this process for a few years now and think it is the most crucial training element to solidify TISP competencies.

- Network and stay current. What are other schools and districts doing? What has been effective in those places and how might that work in your setting? New discoveries regarding the neuroscience of stress, trauma, and learning are occurring daily; how might you curate this data and share with your learning community?

- Share what you are doing. One of the best ways to deepen learning is to share it with colleagues. How might classroom teachers be supported to present at teacher conferences, with their colleagues, district administrators, and/or school boards? Does your school or district encourage staff to network by sharing their work in educator publications and professional social media sites?

- Create a staff TISP mentoring program. Until the Regulation and Support Systems, that element of charged with identifying training and competency standards for the profession, make advances so that teachers and administrators graduate with TISP competencies, you are likely to be starting from scratch with each new hire. How can you utilize TISP skilled staff to facilitate TISP Learning Communities for all new hires? This is perhaps the most cost-effective method to keep the training process going until all sectors of a District are on board the TISP bus.

As previously stated, Districts hold the most influence in getting the ball rolling in an intentional, clear, and measured way that can make or break the engagement of the learning community and TISP’s potential success on behalf of students. It helps to hear the experiences of other administrators. We close this section with an insightful reflection from Rachel. In her story you will hear the dispositions of a trauma-informed educator. Follow along with the process she details, but listen even more closely to how she empathically attunes—how she connects—with her staff as she invites them to join her in this journey. She is modeling a consistent ethic of care, the very relational stance we are inviting each of us to have with students.

A District Administrator’s Story

Our district made a commitment to becoming trauma-informed after the administrative team spent most of a school year learning about the impact of trauma on the developing brain and the resulting long-term health outcomes. Collectively, we all agreed that dedicating time and resources to helping every single member of our district understand how childhood trauma impacts development and the educational experience was the only choice we could make—it was just the right thing to do. As one member of the team stated, “Not sharing this information would be educational malpractice.” Collectively, we all agreed that dedicating time and resources to helping every single member of our district understand how childhood trauma impacts development and the educational experience was the only choice we could make—it was just the right thing to do. As one member of the team stated, “Not sharing this information would be educational malpractice.” Rachel, District Administrator

After that decision was made, the daunting task of shifting perspectives at all levels of our district began. Knowing that this work is about changing the hearts and mindsets of the adults in the system, not fixing the kids, we recognized that we had to take our staff on the same educational journey that the administration team traveled. We had to allow time and space for our people to develop and wrestle with some pretty significant understandings, including realizing the impact of their own traumatic life experiences.

We started this journey by bringing nationally renowned speakers to our small district to create a solid foundational understanding of both the definition of trauma and its impacts both developmentally and physiologically. This burgeoning understanding was deepened and strengthened through an interactive simulation of one child’s early life experiences prior to arriving at school. Throughout this initial phase of the journey, rich conversations connecting new understandings to current reality became a frequent occurrence. Staff were excited to have validation of something that they always knew to be true, but didn’t have a way to define— a confirmation that a child’s life experience did impact their life at school. As staff grew to accept and embrace a philosophy of supporting all students academically, socially, and emotionally, the rich conversations of recognition quickly shifted to the often repeated question, “Now that I know this, what do I do?”

Staff became almost desperate for information and strategies to better support all students now that they understood the impact of childhood trauma. However, it was with intention that we did not provide a laundry list of strategies, but rather sought to deepen understanding of how personal experiences impact interactions with others. It was only in engaging in a continued reflection on personal beliefs and attitudes, and an emphasis on fostering a growth mindset, that staff started to come to the realization that their most powerful tool for supporting students impacted by trauma is their attuned response.

As staff began to realize the importance of remaining regulated and predictable in their interactions with students and others, the journey toward becoming trauma-informed took divergent paths based on levels of personal investment in achieving the larger goal. Just as with any professional learning focus, there are some staff members who readily embrace ideas and opportunities to learn more, and others remain more distant and need additional time and evidence before shifting their thinking. For some staff members, the response to this information was almost immediate— they joined a cohort of teachers dedicated to learning more about the neurobiology of trauma, and creating classroom cultures and instructional spaces that help students build skills to deal with both the stresses of everyday life and traumatic experiences. Other staff members embraced the staff wellness aspect of a trauma-informed approach, seeking to understand and mitigate the effects of secondary trauma, a common experience for school personnel. By intentionally building professional learning opportunities that were differentiated to the needs and interests of the staff, the foundation for effort broadened and strengthened.

Creating the solid foundation was critical as buildings began to design system-wide shifts in their policies and practices to reflect a trauma-informed approach. Intentionally focusing on shifting the system facilitated the alignment of practices, the creation and implementation of a common language, and an ongoing commitment to creating instructional spaces that are safe, consistent, and predictable throughout the entire district. We continue on this journey and are still very much a work in progress, as in learning more about becoming trauma-informed; we recognize there is still so much that we need to learn. It can be difficult maintaining the balance of high relationship and high expectations that is central to this work, but it is so important in providing all of our students the supports that they need to not get stuck in their story, and realize that their past and/or current experiences do not define their future. —Rachel, District Office Administrator

Chapter 7: Exercise 2

Reflections on Rachel’s Story

Rachel shares a powerful story regarding how she and her colleagues came to the decision to implement trauma-informed programming, and then designed a measured, clear, and developmentally sequenced process to move their educational system toward the goal of trauma-informed practice. Her work will illustrate foundational strategies to move an educational system toward successful and sustainable implementation of TISP as will be discussed in our last chapter. For now, reflect on the following:

- What is most striking about Rachel’s story and experience?

- If you could ask her questions, what might you want to know?

- How would you describe the way Rachel conceptualized and spoke of her staff?

- Have you ever experienced administrative role models who you knew viewed and treated their staff as professional colleagues, experts in their own right, and worthy of respect despite tough challenges and the role you merely inhabit in each other’s lives at this moment? “Acting as if” might be easy, as we’ve been coached on how to be respectful in the workplace. But how might an administrator’s internal attitudes of viewing staff as annoyances or threats to progress, or as a force to keep at bay, creep through in nonverbal or covert ways?

- If you notice your administrative staff viewing their coworkers with similar dismissive or demeaning attitudes, how might you inspire them to re-calibrate that inner attitude? Take heart as this is the same process each staff person will be invited to undertake when it comes to their challenging students, as well as their attitudes and relational stance with administrators, other coworkers, and caretakers.

School

As you read through Section I of this text, did you find yourself making connections between situations, events, or escalating behavioral challenges in your school and a student’s history of trauma? We would not be surprised if you found yourself thinking back to a recent interaction or disciplinary event and now acknowledging that change is needed in order for that student to be successful. Let’s shift our focus to taking a critical look at the School. This element includes the activities, tasks, and routines that regularly occur in the school building. It also includes the responsibilities of each school’s administrative team. As we invite you into this section, we encourage you to make a quick list of items relevant to your school’s daily routine, structure, policies, and programs such as bell schedules, lunch schedules, discipline policies, class size, space, etc. One way for you to do this is to begin the day through the eyes of a student. Walk through their experience over the course of a typical day, beginning with the bus ride to school. Then, weave in those things that happen with regularity, but not daily, like fire drills, lockdown drills, assemblies, etc., by adding those to your list. Now shift to consider school policies and procedures that govern student behavioral expectations. One to specifically consider is your school’s discipline policy. Last, how do school staff members interact or collaborate with each other over the course of the day? We imagine you now have a lengthy list.

In this section, we walk you through considerations and elements of Phase I implementation. The notes you take, ideas you jot down, and questions you have will assist you in creating your School Strategic Planning Team and identifying your immediate and short-range goals.

First Steps

Commit. Trauma-informed practices is a complete mindshift and requires a transformative process. In order for this to be successful, you need to fully commit. This commitment begins with building your own TISP competencies, and can take a number of forms in each step of the process. However, without a firm commitment from you to do this work, it will be difficult at best for you to lead your school through this transition.

Lead by Example. As discussed above in the District section, in order for administrators to lead their school through trauma-informed education transformation, they must lead by example by becoming trauma-informed themselves. We really cannot emphasize this enough! Nothing is more awkward than when we are presenting at trainings and it is clear that only the staff are engaging in the activities and readings and not the administrative team. As an administrator leading your school community, I am sure you can see where this is heading. Teachers and staff begin internally asking, “Is this a subtle way of saying our administrators are blaming me for poor student outcomes? Is this important? If I want to implement trauma-informed practices, will my administration support me? Is this a safe space for me to be vulnerable and share challenges as I implement trauma-informed practices?” And ultimately, if teachers and staff perceive the answers to be what they fear most, the status quo rules the day.

Be Vulnerable. Create a safe environment for teachers and staff to be open and vulnerable, and to share what they need to be successful trauma-informed educators. This includes the willingness to deeply listen to your teachers and staff and critically analyze what they are saying. Are there school policies and/or practices that are not congruent with TISP that are creating barriers to successful implementation? Are teachers being held to a specific standard or specific practice that is hindering their ability to connect with students? Have you created a safe environment for your teachers and staff to be vulnerable as they learn and implement TISP? And, if you find the answer is “no” to these and other questions your staff brings to your attention, are you willing to address them?

Build the School Strategic Planning Team. In the previous section on Districts, we emphasized the importance of collaboration with all stakeholders, given that TISP requires system change, not just classroom adjustments. Reread the section discussing the District Strategic Planning Team, as the School team serves the same function but specific to the school’s role in the change process, including the following:

- Identify the various roles represented by staff on the School level, and invite representatives from each of those groups to join the team. This includes classroom teachers from each grade level, and from core subjects as well as the visual and performing arts; coaches; other certified and classified staff; instructional aides; parent volunteers; bus drivers; and licensed mental health practitioners who might serve your school.

- As discussed on the District level, systems and the ways staff work together may all eventually need re-evaluation and adjustment; this requires diverse voices representative of the various programs and student population. Avoid dual representation. For example, if a classroom teacher represents AVID, do not have that person fill two roles—AVID presentation and classroom teacher for that grade level or subject area. Your team needs clear voices and representation.

- The same organizational and communication structures on the District level apply here: Your team might start with a small inner group, but as positions fill, design an organizational structure allowing subgroups to work independently of the large group with a clear process for all parts of the team to provide updates for the team and the larger School community.

- School-level subcommittees would include the following designed to address various role-specific needs: classroom teachers, school counselors, school psychologists, instructional aides, parent volunteers, and classified staff. For some of these subgroups, a few gatherings a year might be good enough as you work through common readings, or discuss what implementation in your area might look like. For others—for example, school counselors—after you meet initially on your own, many of your remaining meetings might be with classroom teachers, as these two roles will be required to readjust interactions and systems of mutual support. A system of centralized information sharing will help you figure it out as you move along.

- School subcommittees also include special focus agenda items, such as re-evaluation of student management policies, lunch room processes, school lighting and use of space, etc. Some of these tasks require larger workgroups than others, but all of them require team members committed to developing TISP competencies. For example, a team doing the initial evaluation and investigation into behavioral management policies needs to include classroom teachers from various grade levels, school administrators, and those most responsible for responding to students who cannot function in the traditional classroom. But if the persons on this team have not been participating in a TISP training and learning process, they will not be able to evaluate and create new processes that are TI congruent.

- The School team needs to have representation on the District team in order to foster communication and not duplicate efforts. It is ideal if a district-level administrator and a Community representative from the board are invited to participate in various aspects of the School Strategic Planning Team as well.

- And as indicated for the District level, it is imperative that School administrators identify themselves as TISP-in-training. This process will fail if we think it is merely about classroom teachers changing the culture and practices of the classroom. School administrators must change their mindset and practices, as well as lead by example.

The initial tasks of the School Strategic Planning Team also mirror District initial tasks. Most notable:

- Engage in a learning process to inspire deeper awareness of what TISP is, and discernment regarding where to begin.

- Design in-service activities and events to build interest and momentum among your school staff. Watch for signs of staff who are already all-in and willing to serve on the team.

- Gather an initial School Strategic Planning Team to discern method of implementation. If a District team is already in place, school administrators or other members of the school team may already be in communication regarding decisions for initial implementation plans. For example, your school may have already decided to train one grade level or one teacher cohort group based on a District-level strategy. Or, you might have decided to change school-level systems, daily rituals, and routines during Year 1 as classroom teachers develop an implementation Action Plan to begin in full swing during Year 2. Either way, design the immediate and short-range goals based upon your ultimate goal or mission statement.

Short-range goals for the School Strategic Planning Team include the following:

- Re-evaluation of each staff’s role according to a trauma-informed ethos. Much emphasis is placed on the role of the classroom teacher in Classrooms, discussed in Chapters 8 and 9. Do not neglect focusing on changes needed in other certified and classified roles.

- Re-evaluation of school-based practices as discussed further in this section. Most important is designing rituals, routines, and processes congruent with TISP purpose and dispositions as it relates to Phase I and II tasks. The implementation of these changes is largely driven by the administrative team, as co-designed by the School Strategic Planning Team.

Provide Education and Training. Recently, I (Brenda) was invited to meet with an administrative leadership team to talk about trauma-informed practices. During my time with the team, I was offered a tour of the school, which included a calming space in the main office and several classrooms where calm-down spaces had been created. I learned that the school made the decision to fund these spaces in all classrooms for consistency. The calming space was inviting and included sensory objects for a child to engage with. I approached the classroom teacher and asked about his experiences thus far implementing the calming space. How did he introduce it to students? Were students using the space? What, if any, impact did this have on his students? And, why did he choose to have this added to his classroom? Unfortunately, his response was disappointing, but not unexpected. Yes, students were using the space, but it really had little impact on the classroom management challenges he identified. When I asked if he had received any training on why calming spaces can be effective, he said no. He used the space as a “time out” center where he sent students to reflect on their poor choices or behavior. This teacher had resources in his classroom that would support trauma-informed practices, but he had received no any educator and training, and did not know how to use these resources in a scaffolded way to help all students as part of a larger social-emotional coaching process. It is no wonder he did not see this as being effective.

In Chapter 5, we cautioned that not all things labeled trauma-informed are authentic. As you may have already discerned, “trauma-informed” or “trauma-sensitive” sells. Each of us has attended workshops and conferences, read school implementation books, and reviewed discipline programs that claimed to be “trauma-informed.” However, not all of them are the real deal. As you may have already discerned, “trauma-informed” or “trauma-sensitive” sells. Each of us has attended workshops and conferences, read school implementation books, and reviewed discipline programs, that claimed to be “trauma-informed.” However, not all of them are the real deal. Other pitfalls include the idea that a simple set of strategies is all that is needed; good money is then spent on energizing—and worthy—strategy trainings, but these are prematurely offered in the absence of understanding the conceptual elements underlying trauma-informed practice. With limited resources to transform your school, it is important to maximize those resources and not fall prey to a speaker, trainer, or program that is not truly trauma-informed, or presents an unrealistic vision of how the competencies and transformation process takes place. This is also true of mental health professionals. As mentioned previously, not all licensed mental health practitioners, or those with social and behavioral science competencies such as school counselors and school psychologists, are trained in trauma-informed response. Therefore, choosing the right people to train school staff is critical. We encourage you to do your homework and select well-trained professionals to work with your school.

Are you familiar with the proverb “Give a [person] a fish and you feed [them] for a day. Teach a [person] to fish and you feed [them] for a lifetime” (Tripp, 1970)? Consider this proverb in light of trauma-informed practices. Knowledge of neurobiology and best practices in response are foundational to Trauma-Informed School Practices. As a teacher, I (Brenda) can appreciate the desire to receive classroom strategies that could easily be implemented in the classroom tomorrow. However, as shown in the example above about calming spaces in classrooms, without a conceptual understanding of the neurobiology of trauma and best practices in response, it is nearly impossible to discern how a specific strategy could work for your group of learners. As a teacher, I (Brenda) can appreciate the desire to receive classroom strategies that could easily be implemented in the classroom tomorrow. However, as shown in the example above about calming spaces in classrooms, without a conceptual understanding of the neurobiology of trauma and best practices in response, it is nearly impossible to discern how a specific strategy could work for your group of learners.

To support the development of TISP competencies, we created a certification program for educators (Appendix C). The program teaches participants how to fish by acquiring the knowledge, skills, and dispositions of trauma-informed competent educators. Strategies are introduced once the educator can conceptually assess their appropriateness and manipulate their prescribed procedures to contextualize them for their students. And the implementation of those strategies co-occurs with group supervision and peer consulting. Our training methods are born from our own observations of open-minded educators riding the wave of excitement, only to bump up against obstacles that they were not equipped to foresee. While this is all typical and expected on the road to system or paradigm change, we think the urgency and interest in TISP now requires more emphasis on thorough and reliable training processes.

Create Space. Once you have a team of educators participating in training, it will be important to create space for each subgroup per role to gather to support each other. For classroom teachers, this could include authorizing substitutes so that the group can visit each other’s classrooms and watch a specific lesson, or see how a strategy is being used, or how a teacher is guiding her class through social-emotional learning. For the student discipline evaluation subcommittee, it could mean engaging in a Professional Learning Community (PLC) based on common trauma-informed behavioral management system readings, visits, and interviews with trauma-informed districts and schools, while beginning the revisioning process by crafting a student management mission statement. Coaching and peer support can be instituted once a program redesign is in place. By observing others, we gain ideas and insights into our own practice. We also support the work of our colleagues by providing feedback. In addition to observing each other, PLCs dedicated to elements of trauma-informed practice become an indispensable tool for developing and deepening TISP competencies for all staff in your school.

Evaluate. We encourage you to spend time evaluating the efficacy of the TISP transition and its impact on your school community. This evaluative process also connects with the recommendation above on being vulnerable and listening to your school community. We encourage you to evaluate current roles and job descriptions, efficacy of transition, visuals, rituals, and discipline policies in your school. In Chapter 12, we will explore this topic further.

Roles and Job Descriptions. Let’s think about this category holistically. For example, how does your school view the role of parents/guardians in the school community? Is the way in which your school views their role, and the ways in which they have been invited to participate, congruent with TISP? How could you rework their role to support TISP? We recommend that parents receive an orientation to TISP as part of the preparation process to become classroom aides. We will discuss this further in Chapter 10.

And, for school teachers and staff, how do they interact with one another currently? How does your school, under a TISP model, need those groups to interact and support one another? Is this model supporting your school community in strong ways? If not, we encourage you to begin a list of possibilities. What do you want those roles to look like? Trust that as you absorb this text and other trauma-informed school writings, gather a team, and work through the TISP Tri-Phasic Model disposition and tasks, your strategic team will have plenty of thoughts regarding how to answer these above evaluation questions.

Efficacy of the Transition. Recently, I (Brenda) presented on our TISP Tri-Phasic Model at a national conference for K-12 schools. I attended a session presented by administrators on their experience moving to a trauma-informed model. They shared what they had learned from their own trial and error, and made recommendations on how others may want to proceed. As I listened to their presentation, I was excited about the work that they had done and how the changes they made were indeed supporting students. During their presentation, they shared concern about their behavioral discipline data and the fact that they were not seeing the improvement they had hoped. A few questions from session participants during their question-and-answer piece revealed the answer; unfortunately, the administrators lacked understanding of the neurobiology of trauma along with best-practice response strategies. They knew that their students had experienced significant adverse childhood experiences (elevated ACE scores) that were likely impacting behavior. However, they were unable to connect ACES to its role in undermining neural integration processes, and did not know how to design behavior management systems according to best practices in response. Instead, they continued to use current practices adopted by their district, thereby missing a significant piece of the puzzle. What a great example of evaluating the efficacy of transition! This group gathered and analyzed their data, and with humility shared what they just couldn’t understand. By getting to this point and asking folks to review their data with them, they were able to identify the missing piece. We encourage you to do the same! We will explore this topic further in Chapter 12.

Early-stage tasks of the School Strategic Planning Team include a number of elements congruent with your short-range plans and are highlighted in the TISP Tri-Phasic Model disposition and task list. Basic to your particular goals are the following three tasks:

Visually Assess Your Learning Environment. The hallmark challenge of students today is to build neural networks to increase integrated thinking, feeling, and intentional behaviors, all of which are basic to executive functions needed to learn. For many students, their capacity to regulate environmental stimuli, whether in the emotional-relational environment or the physical environment, is challenged. For many students, their capacity to regulate environmental stimuli, whether in the emotional-relational environment or the physical environment, is challenged. For students who cannot filter noise, cramped classrooms, echoing large spaces, and other ambient noise will constantly activate their stress response systems. For those with highly attuned visual sensors, spaces with lots of supplies and decorations sprinkled with important messages and reminders will be overwhelming. Many others are impacted by fluorescent lights and the lack of natural sunlight. Most schools today do not have windows that open, and lack fresh air; think of how nice it is to see sunlight shining into a room, catch a passing rain shower, or breathe in fresh air flowing through a window. These are neurological boosters that help all of us enjoy our surroundings, and feeling a spark of joy makes the task at hand more pleasurable. Many schools today lack these basic elements of welcoming environments. This requires us to be creative.

This task asks team members to consider the physical space in your school and in your classrooms. What messages do they convey? Are they congruent with TISP? Consider what visuals are present that need to be changed or created to reinforce the following:

- TISP building blocks of care, community, and the importance of each class member or student. These visuals will reflect the class or school’s TISP-informed motto or guiding values.

- Psychosocial learning tools, namely how our brain works, the importance of our emotions, and how to increase tracking of thoughts, feelings, wants, needs, and behavioral choices in response.

- The teacher and students’ co-created processes for identifying need states, helping out a peer, tools at everyone’s disposal, and other relational processes you have implemented.

Continue the evaluation process by asking the following questions:

- What wall decorations and other physical display items are currently prominent that are contrary to the messages you are trying to create?

- What current items might need to remain but not be centrally located?

- What items (resources) could be stored in cabinets or behind curtains on shelves to simplify the visuals in a particular space?

- What items need to be removed from walls or shelving, and what items need to be changed, such as lighting, seating, furniture arrangements, or wall paint?

- What is your source of light, and is there a way to soften it even while creating bright well-lit spaces where needed?

- How does sound travel through a particular space, and are there ways to contain or muffle noise where large groups of students need to meet?

In her book Reaching and Teaching Children Exposed to Trauma, Dr. Barbara Sorrels (2015, p. 165) recommends the following for classrooms:

- Neutral color on the wall

- Subtle or no pattern on floor covering

- No more than two-thirds of the wall space covered with posters, bulletin boards, or materials

- Child-sized furniture in natural colors

- Materials stored in natural-material baskets

- Overstuffed chairs and loveseats for reading and resting

- Displays made of natural materials such as interesting rocks, pinecones, wood pieces, and so on

- Cozy spaces or interest centers to divide up the room

Evaluate and Design School and Classroom Rituals. Just as you did with physical space above, examine what rituals you have in your school. Think about those that occur daily, weekly, and on occasion throughout the school year. A resource rich with ideas is The Morning Meeting Book by Kriete and Davis (2014). Do these ritualactivities mirror the goals of a trauma-informed school, congruent with how we are identifying the nature of students’ need and best-practices in response? Your evaluation will help you identify what to change or implement congruent with TISP. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Check-in grounding and attunement rituals: Many schools prefer to design a welcome and focusing ritual each morning where students reflect on how they are doing by taking a thought-emotion-physical feeling scan, to practice attuning to self and others and the giving and receiving of care, and to build a sense of safety and stability. And then the group shifts into the goals of the day or class period. Many of these same schools have end-of-the-day rituals for transitioning out of the hard work of the day, grounding bodily responses, and giving the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) a few minutes to rest thanks to the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) before they head on home or to their next set of daily activities.

- To ease transitions, classroom teachers often design rituals at the beginning and end of a class, day, or week, and at the end of an academic term prior to an extended break. Some rituals may be more in-depth, while others are quick anchoring activities. We offer resources at the end of each chapter. But the conceptual elements underneath each activity are emphasizing self-awareness (internal neural network processes as detailed in Figure 2.5), self-rescuing or soothing, showing care for peers, and acknowledging that life is hard, but we can find help, fun, and joy along the way—all within a spirit of curiosity, care, and hope that they can increase their sense of well-being.

- What rituals give structure to a day, a week, and a season, knowing that the repetition creates a sense of reliability, stability, and predictability?

- What is already in place that might be appropriate but not as a grounding, skill-building, or community-focused ritual, and hence needs moving or replacing? A teacher shared how she was expected to greet students at the door with an immediate message regarding the behavioral expectations of the class and the learning goals of class for that particular session. TISP is asking that students be greeted at the door with a metaphorical Welcome sign, with a few moments of personal check-in, and then a shift in focus to the day’s agenda.

- Nurture your own creative strategies by scanning other implementation books and searching YouTube, Pinterest, or other social media sites dedicated to trauma-informed school practice.

Evaluate and Adjust Student Management Processes. Have you considered the philosophies informing your current discipline policies? We invite you to critically analyze your current practices. What do you want your discipline program to do? We revisit this topic in Chapter 9. But for now, we offer the following to get you started:

- Desired Mindset/Internal Framework: What is the goal of your behavioral management system? It is most often revealed in both overt messages (mission statements) and covert messages (attitudes and dispositions of the staff enacting the policy; end result as revealed in student responses).

- Method for Teaching Students and Staff This Mindset: This includes practices and approach. How is it working for students and staff?

- Techniques, Tools, and Resources to Teach and Support the Student: What are they teaching students? This connects with the overt and covert values and goals of the program.